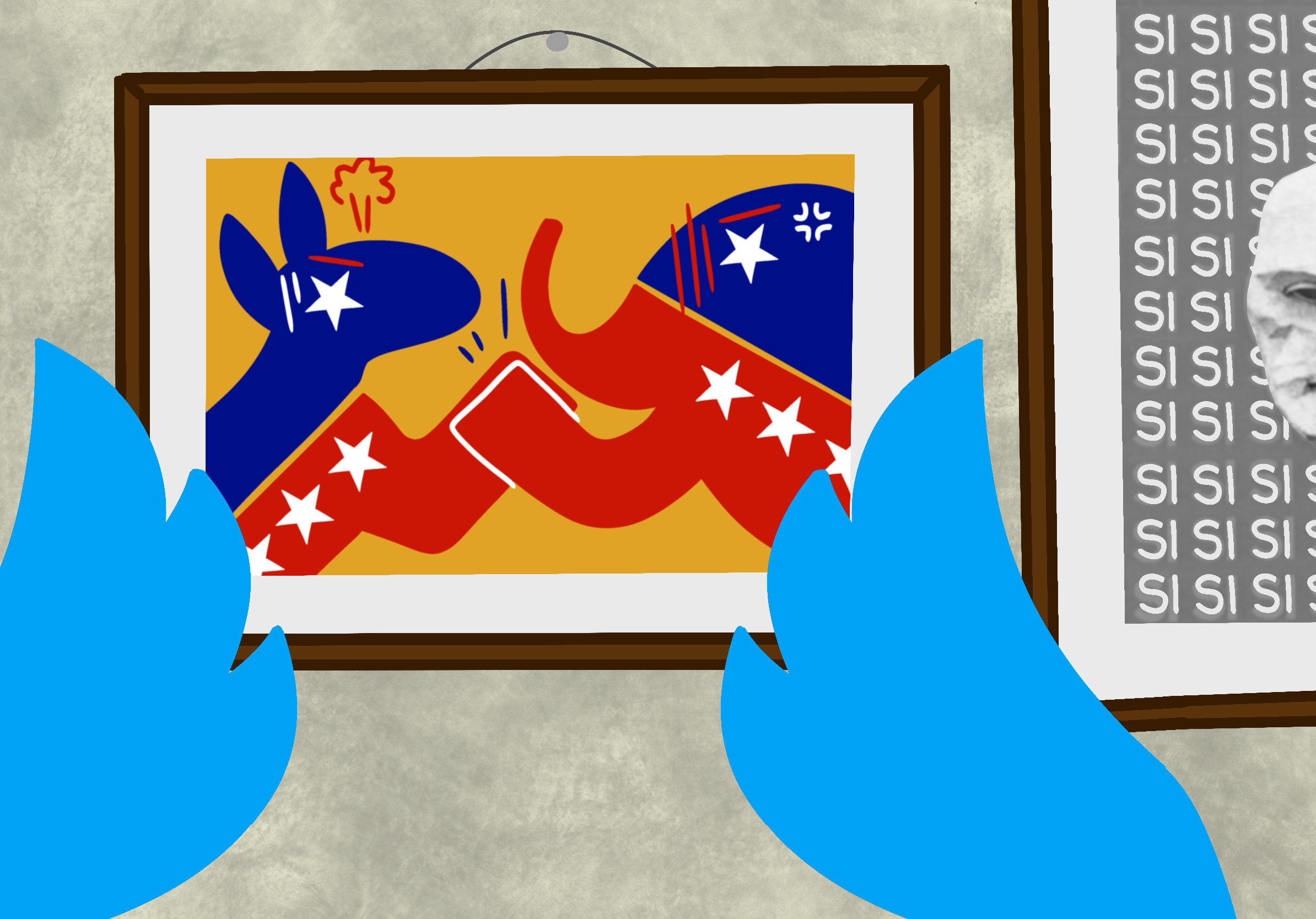

The cultural divide between opposing sides of the political spectrum has grown tremendously over the past several years. Whether the result of the increasingly detached nature of online discourse or political shifts toward extreme politics in the Western world, this separation has growing ramifications on the world we live in.

One of these impacts is the supposed loss in viability of the “politically neutral” stance. Political neutrality, in this context, means a voting record or public perception which is neither Left nor Right, Conservative nor Liberal, or Democrat nor Republican, but one that can be found somewhere in the nebulous space that exists everywhere else along the political spectrum. Often, this is referred to as a political “independent”, signifying that a person supports a candidate that is “independent” of the major ideological divide that is present in North America.

This loss in viability is frequently discussed in online political spaces and more broadly in popular culture. In my experience, politically extreme groups can often only agree on one thing: their hate for a neutral group. Despite this, political neutrality continues to have an increasingly important role in the contemporary political climate.This growth in importance largely stems from one factor: the shift in political discourse. This shift was not from one end of the political spectrum to the other, but a change in the way that politics themselves are discussed.

Broadly, I believe this is a result of a shift from generally economic party platforms, which focus on things like the federal deficit and tax rates, to generally cultural party platforms, which concentrate on social issues, like LGBTQ+ rights and immigration. One of the first parties to make this shift was the Democratic Party in America, especially within former President Barack Obama’s successful years. Obama campaigned victoriously on issues like abortion, same sex marriage, and pay equity for women.These cultural issues meant that politics were no longer an analytical decision undertaken every four years on what party provided the greatest personal benefit, but a broader moral decision, the results of which have outsized social ramifications. All this amounted to people taking not only their own political choices more seriously, but the choices of others as well.

While taking politics seriously is not a problem, the political factionalism it generated en-masse certainly was. This political factionalism originated in simple social signifiers.

As politics became an extremely personal matter, people began distancing themselves from those they disagreed with politically. This progressed into the active “policing” of social relations by society, largely through social media platforms, with the express purpose of filtering out opposing views. This form of policing could be seen at its most extreme during the height of “cancel culture” in 2018. Broadly, this also signified a shift from viewing opposing political views as mere personal differences in ideology to fundamentally invalid dogma.

Naturally, this self-policing was extremely complex, as individuals are almost never diametrically opposed to anyone because politics is not binary. As such policing began adoption en-masse, it was necessarily simplified by public dialogue so that it could be almost formulaically applied to anyone, by anyone.

This simplification gradually began eating away at the political “center” as it categorized many of these people into “the Left” or “the Right” binary, despite their potentially multi-faceted and varied political opinions. In popular discourse, there was no longer a political spectrum, but two definite sides that were wildly opposed to each other.

The polarization of day-to-day political life has granted many opportunities to each respective ideological group. Among them was the ability to codify the long-held sentiment within the deeply politically inebriated that the opposing side was not only wrong, but defective in principle.

This invalidation was ratified by the characterization of the belief that members of the opposing group are inherently evil, and their goals are solely motivated by malice. This allowed the divide to grow even wider, as it became critical that people were deeply politically invested to assure that they were not part of the “evil” side. This is exemplified by the 2016 Democratic campaign website, which foregoes an easily accessible campaign promise section for a section painting the GOP’s nominee, Donald Trump, as someone who is evil. Ironically, this political investment did not need to be backed by understanding theory, or even agreeing with any theory broadly, but instead could be constituted entirely by lip service.

Treating lip service as political involvement greatly exacerbated political problems. Once political affiliation could be made at the cost of forsaking your own beliefs while taking

advantage of a swathe of social benefits, this trend was sure to spread. Whether consciously or not, thousands of people became “leftists” overnight, without ever interacting with any theory critically or making any concerted effort to change the world around them. For them, the choice was not a political one, but a social one.

While this certainly had some positive effects, like the uplifting of certain marginalized communities, these empty promises spelled doom for left-wing cultural parties worldwide. Post-pandemic, as society began to shift away from “cancel culture,” being “leftist” lost its allure for many people. Its social significance faded, taking with it millions who had been committed to the democratic cause by word only.

Somewhat expounding the severity of this shift, and thus the severity of the Democrats’ mistake, was the level of support that Trump commanded after his re-election. He not only won the Presidency, but also the popular vote —two separate things in the US due to quirks of the electoral system — and currently enjoys a House and Senate majority, giving him an exceptional and rare level of control.

Instead of a slow, natural growth toward increasingly leftist views that seek to reform society, a short boom in left-leaning ideology occurred, immediately followed by a cataclysmic reversal.

If leftist cultural platforms sought long-term societal change that uplifted minority groups while maintaining and reforming social institutions, they failed.

Now, as increasingly extreme right-wing groups vie for power throughout much of the developed world, we can see the Left pinning their failings on the ever-growing share of independents and right-wing voters. For many, this could seem natural; independents represent original thought and political opinions, the opposite of the almost blind adherence to a corporate agenda which characterized so many cultural platforms in the 2000s.

It is here that the root of the supposed “inviability” can be found, but it is best exemplified by the Democratic Party of America. In the Democratic Party, many voters understand that political neutrality is antithetical to their own party, but misunderstand the characteristics of their relationship, and therefore often form false equivalences.

To these party members, their almost archetypical nemesis is the GOP, or Republican party. To them, the GOP represents everything they fight against, almost to a tee. This gives them the impression that they are two great polar forces, tangled in bitter struggle. Instead, they must understand that they are merely two sides of the same coin: a corporate party vying for power.

As such, a false equivalence is born: if independent voters are the antithesis of Democrats, and Republicans are their bitter enemies, then they are equivalent. This faulty logic leads them to misunderstand independents as hopelessly incorrigible individuals who do not understand the power they command. Instead, they could be the future of a truly powerful leftist party grounded in critical thought and understanding, not blind obedience. If Democrats do not understand the characteristics of this paradigm, they will continue to alienate what could be powerful new foundations for their party.